Like many of their peers last May, two young women, both 21 years old, celebrated their graduation from North Carolina universities. What happened then was fairly typical for that momentous day: They put on their caps and gowns, walked the stage, posed for photos with their families and friends, and posted about the milestone on social media.

But something sets the two apart from many of their fellow graduates. They share a particular burden of having to navigate the visa system for the rest of their lives just to stay in the U.S., because there is no path to citizenship for them.The two women have lived most of their lives in the U.S., but they were born in India. Their parents brought each of them to the U.S. when they were five and six years old, respectively, attained the H1-B or skilled worker visas, and applied for green cards when they became eligible. However, due to the incredibly long backlog of green card applications, especially from Indian H-1B visa holders, their parents have waited well over a decade to receive them.

In that time, the two women aged out of their H-4 visas, which are held by children of H1-B visa holders. Ahead of their 21st birthdays, they applied for F-1 student visas.

"(My family) always thought we'd get our green cards well before I went to high school," said Fedora Castelino, who recently graduated from N.C. State. "My parents never thought we would ever get to the point where I was going to be directly affected by it."

After graduation, F-1 visa holders are granted a 60-day grace period to figure out their next steps. The other young woman, Shristi Sharma, a Robertson scholar who graduated jointly from UNC-Chapel Hill and Duke University, was able to extend her F-1 status by taking a job with a company to do work related to her computer science degree. Castelino, however, elected a different path. Earlier this year, she applied for a religious worker visa and was able to get approved for it in mid-July.

But she waited months for an answer, not knowing if she would get approved or have to self-deport to another country. Without a work visa, Castelino also couldn’t seek employment in the U.S.

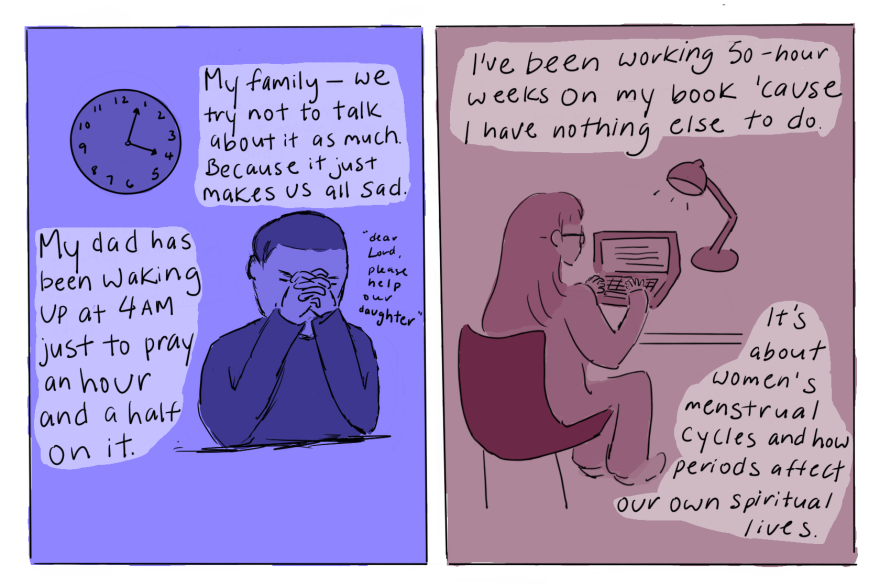

"My friends say 'you know, it's great you can stay in the country at least until you hear back,' but what if I don't hear back for another year?" she said to WUNC in early July while her visa application was pending. "That's waking up every single day, having no job, no school, like nothing to wake up for every day. It's very mentally taxing. What do I do with my time?"

The conventional path for "documented dreamers"

Immigration advocates estimate that there are at least 250,000 children of long-term visa holders – sometimes referred to as "documented dreamers" – in the U.S. This is, in part, due to the 7% limit the U.S. government puts on the number of green cards issued to individuals of any country per year. Because so many skilled workers arrived in the 1990s and the 2000s, especially from India and China, it created such a massive bottleneck of folks who've applied for permanent residency, to the point where many of them likely won't receive one within their lifetimes.

Ironically, many of the children they brought with them, like UNC and Duke graduate Shristi Sharma, see themselves joining the same long line that their parents have waited in for years for a green card. Sharma arrived in the U.S. when her father enrolled at an international university in Iowa in the mid-2000s and lived most of her life in the Midwestern state until she moved to North Carolina to attend college.

Sharma's ambition is to work in cybersecurity, ideally for a federal agency like NASA. But not being a permanent resident, she knows she does not qualify for such public sector jobs, so she applied for many private sector jobs in the fall of her senior year. Sharma estimates she applied for around 250 positions, many of which she received immediate rejections from.

"As soon as you select the box that says you need visa sponsorship, your application automatically gets rejected," Sharma said. "I would get rejections within 20 minutes of applying to places. Right now in this (political) climate, very few employers are willing to go through the legal processes required to take an immigrant into the workforce. I struggled with that for many months."

Sharma was eventually offered a position at a Texas-based cybersecurity firm, which she started in early July. Since her position was related to her bachelor's degree, she was qualified to use a work authorization benefit of the F-1 visa called Optional Practical Training. It essentially allows student visa holders to stay in the U.S. for another year and it can be extended for two additional years if it is STEM-related (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) work.

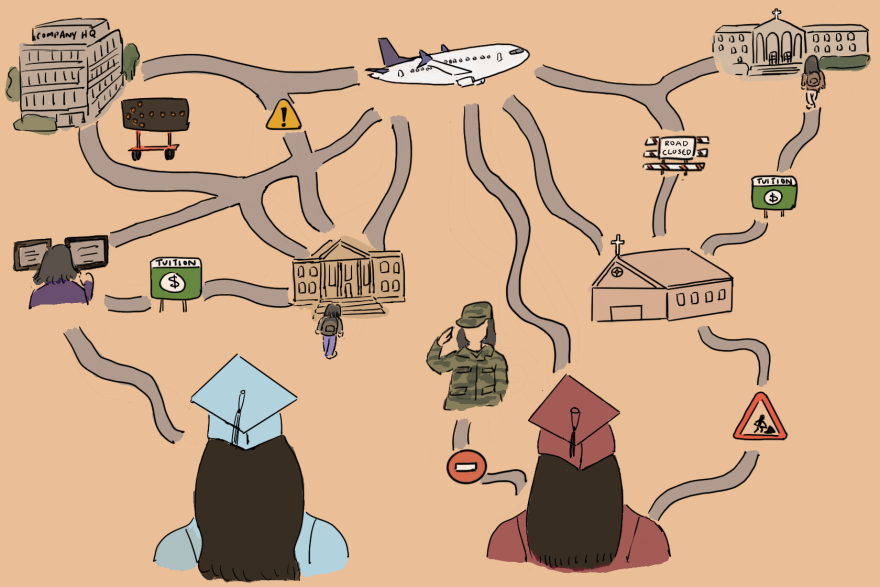

But beyond doing OPT for three years, Sharma said she doesn't have a plan. She will most likely consider three options: Go back to school for an advanced degree, enter the lottery for a H-1B skilled worker visa, or self-deport to go work in another country, like Canada or the United Kingdom.

"It's very senseless," Sharma said, "because I've gone through an entire American education, from kindergarten through now college and now I'm entering the workforce, getting trained in America, paying American taxes – and take all of that and move to another country."

Morrisville City Councilman Steve Rao has heard from many Indian visa holders who express this type of frustration and anxiety about the immigration system. People from India also make up the second largest group of foreign-born residents in North Carolina, after those originally from Mexico, according to demographers at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Rao strongly believes that without immigration reform, the U.S. will lose talented workers like Sharma to other countries and that will deeply hurt the economy.

"People may not want to come here anymore because of (immigration) being taboo," Rao said. "I'm concerned that eventually you would see a brain drain during a time when we have a shortage of skills and talent, and technological innovations are accelerating at an unprecedented pace. Now is a time when you want people there doing those jobs."

A more unconventional path

As many young people do, Fedora Castelino realized that she didn't want to seek a career related to her major, which was biology.

In 2021, Castelino began college at home, like many students did during the early days of COVID lockdown. She recalled feeling then like she "didn't have a foundation, like my own identity of who I was," and later, when students returned to campus, she felt disoriented and had a hard time waking up in the mornings. That is, until a close friend helped her reconnect with her faith.

"I fell more in love with my faith and more devoted to it during university," Castelino said. "(During COVID) I really did hit like a rock bottom in my life and I was pretty sure I was being called to step away from a career in science to fulfillment in religious work."

Castelino, who was raised Catholic, wants to serve the parish she grew up with by growing their young adult membership.

"I'm hoping to do young adult ministry, so working with 18 to 35 year olds," she said. "The church that I go to now, we don't have the biggest presence of 18 to 35 year olds."

So Castelino applied for the R-1 visa to do exactly that. But the months she and her family spent waiting for approval were agonizing, she said.

"My dad has been waking up at 4 a.m. to pray, just to pray for an hour and a half on it," Castelino told WUNC in early July, before her visa was approved. "And my mom tries to think all the time, try find a new solution. But at this point our hands are tied. We just can't do anything but wait."

On July 14, Castelino received news that her visa was approved, allowing her to work at her church and stay in the U.S. for the next two years.

Greensboro-based attorney Jeremy McKinney says his practice has worked with many teachers from India whose children encounter the same challenges as Sharma and Castelino. Most of the time, he said, the children would pursue a STEM degree in college and apply for OPT, like Sharma did.

Regarding Castelino’s choice to pursue a religious worker visa, McKinney said that is a more difficult path for a documented dreamer since one has to "demonstrate non-immigrant intent." That means they have to show evidence that they have a residence, family connections, employment ties and financial ties to their "home country," or else the visa will be denied.

"They need to show that they have a residence in their home country that they have no intention of abandoning," he said. "This creates issues when you have basically been (in the U.S.) since you were seven years old."

Castelino has considered pursuing a master's degree in theology, which would help get her back on a student visa. However, she currently can't afford to enroll in such programs, nor is eligible to receive most forms of student financial aid or federal student loans. And since she does not have work authorization in the U.S., she's not able to earn money to help pay for that education.

Despite all these challenges, Castelino expressed tremendous pride for the country she grew up in. She dreams of enlisting in the military or getting trained to become a police officer, even though such dreams are out of reach for someone who doesn't have permanent residency.

"I think there's a lot of misconception that people come to America because they have nowhere else to go. People think immigrants are here because we want better jobs or better opportunities, but the truth is we love America," Castelino said. "My boyfriend is an international student too and we want to raise a family in America one day. We love what America has to offer and we want to contribute to the economy."

Walking a fine line in a political environment that's hostile to immigrants

Lawmakers across the country have attempted to pass various bills in recent years to address the issues faced by long-term visa holders and their children. For example, the RELIEF Act, which was introduced in 2020, would increase the number of immigrant visas available, eliminate the 7% limit per country and would prevent dependents from aging out of their visas when they turn 21.

In 2021, the America's Children Act, a bipartisan bill co-sponsored by North Carolina Congresswoman Deborah Ross, was introduced to help give long-term residents like Sharma and Castelino a path towards permanent residency in the U.S. It didn't pass then or when it was reintroduced in 2023, but a new version of that bill is expected to be reintroduced this year.

But under the climate of the Trump Administration, immigration advocates are not certain there will be much progress.

"I am doubtful," said McKinney, who is also the past president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association. "The current administration is really at war against immigration. Every step of the way, they are putting roadblocks and hurdles in the way of people seeking to do things the right way and go through the legal system."

"I've been practicing law since 1997 and I've gone through lots of ups and downs, including the first Trump administration," McKinney added. "But 2025 is next level. I have testified twice before Congress about injecting basic due process into our immigration court system."

The heightened tensions this year around immigration issues, ICE raids that have targeted Indians in the Triangle area, and swift actions to revoke visas from international students have many visa-holders like Sharma on edge and treading carefully. A few weeks before graduation, Sharma planned to fly to Costa Rica for a scholarship-funded trip to spend several days researching the local ecology and environmental sustainability practices. But on the day before her trip, she decided that her safety was more important.

"I canceled my entire plan because I was 15 days away from graduation," she said. If I wasn't allowed back in the country, I would miss my finals. And if I missed my finals, I couldn't graduate and no one's going to hire me if I have seven-eighths of a degree."

Sharma and Castelino also work with Improve the Dream, a volunteer-run organization that supports children of long-term visa holders. In doing that work, Sharma's aware she's making herself a fairly visible advocate on an immigration-related issue, but she feels that it's still important to speak up for those in her situation.

"This is a really uncertain time for immigrants and that has made a lot of people become kind of reclusive in their day-to-day lives to make sure they're not drawing attention to themselves," Sharma said. "I think it's important that we remind ourselves that it's still OK to continue to express ourselves and do all the things we used to do when we didn't feel an incredible amount of fear – while also being cautious and strategic."