Backdrops and props for theater productions are normally temporary and change frequently. But a 155 year-old hand painted curtain at Thalian Hall in Wilmington has survived – and is thought to be the oldest stage curtain in the United States.

Stage curtains are not created to last. Scenery gets recycled and thrown away over the years, in an ephemeral spirit akin to the art of theater itself. Contrary to the transient intention of its maker, one piece of canvas has survived over a century and a half. Thalian Hall in Wilmington, North Carolina houses what is believed to be the oldest stage curtain in the U.S. Zannie Owens has more.

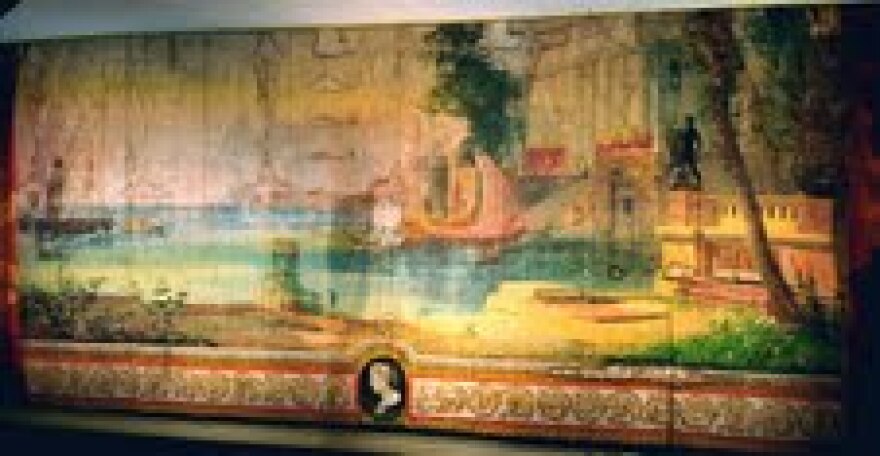

William Thompson Russell Smith, a Scottish painter from the 19th century, is primarily remembered for rendering images of Pennsylvania landscapes into paintings that have become iconic. Aside from these works, Smith also produced theatrical scenery. One of these colorful, canvas masterpieces still hangs in the ground floor lobby of Thalian Hall today where visitors can view the 150 year old curtain. Tony Rivenbark, the executive director of Thalian hall, opens the curtain on the history of this artifact.

“This curtain was the front curtain for the theater up until the turn of the century around 1900. And then the stage opening was expanded and they added some side panels. Then there was a change in the theater again in 1904, then again in 1909, so somewhere along the line it was decided to no longer use that curtain, but it never got thrown away. So it would be sort of folded up and put away, and be forgotten, and then it would be discovered again, and that’s what happened over and over and over again. It’s sort of interesting that in the end it continued to survive.”

The curtain was painted in 1858, the same year that the Thalian Hall was built. Rivenbark says that the dimensions of the curtain have changed, along with the theater itself.

“We have the bottom half of the curtain, which I think is about fourteen feet of the bottom curtain, the whole curtain was 23 feet, we think it was 23 feet tall when it was first painted. The top half of the curtain, which is mostly sky, was taken off probably in 1939, when there was another remodeling of the theater.”

Smith often used classical motifs in his work, the scene on the Thalian curtain depicts Greek dignitaries sailing to consult an oracle.

“It’s a large painting of basically a temple on an island in the Aegean Sea in Ancient Greece. The chief personages of the Ancient Kingdoms of the Aegean Sea are arriving to make sacrifice at the Olympic Games at the Temple of Apollo, so it’s a classical painted scene.”

Only three of Smith’s other pieces for theater have withstood the test of time, and are currently in Philadelphia. Most curtains weren’t meant to be saved, nor did they have a long lifespan. A lot of these curtains either fell apart out of use, or fell out of style and were discarded. David Rowland, president of the Old York Road Historical Society in Philadelphia, expresses the impermanence of theatrical scenic paintings.

“Given their size, and how much space they took up, most theaters don’t have a lot storage capacity. Old scenery sort of just gets the heave-ho out the door. So it’s really quite rare and wonderful that this piece of curtain in Thalian hall has survived since 1858. The other two large drop curtains, there are two large drop curtains and sort of a runner, the two large drop curtains here in Philadelphia date from 1890 and 1892, so very much at the end of Russell Smith’s painting career.”

In 1858, the curtain cost $200. Today, it’s estimated that the painted canvas is worth $38,000. Rowland says the fragility of curtains from the 19th century can be attributed to the popular painting materials of that period, which were intended for temporary and interior decoration.

“Well the curtain is painted on canvas, Russell Smith is known to use only the finest of materials when he did his curtains, and he would sew the canvas together himself. It’s painted with what is called distemper: which is ground color with a glue sizing base that allows the paint to be spread and then adhere to the canvas. It’s not like traditional oil paint, which uses an oil base and then dries with a sheen. Distemper uses a glue base, and then dries with a matte finish.”

Although Smith’s paintings are considered very valuable, they are also reasonably priced since Smith was not a part of the Hudson River School, a popular school of thought for American painters prior to 1900. In light of this fact, executive director of Thalian Hall, Tony Rivenbark, claims Smith was still a prominent American painter.

“He was a very well known painter for his day, his paintings are still on the market, they cost about three or four thousand dollars apiece. So he was a very well recognized artist, he and not only him, but his whole family. His wife, his daughter and his son were all important painters.”

In the 1970’s, much of the Smith family’s work went into the market as a result of the dispersal of their estate. Unlike most old art that undergoes numerous transitions in ownership, the Thalian curtain has remained at the performance hall in Wilmington for 155 years. Tony Rivenbark, executive director of Thalian Hall, has done extensive research on the history of theater in Wilmington, and stresses the historical significance of both the curtain and the place where it resides.

“Thalian hall was built in 1858 and has been in continuous operation as a theater since that time, so it has an extraordinary history as a theater in this community. It was a place where many touring artists played, some of the greats were like Lillian Russell, Mont Adams, Joseph Jefferson, James O’Neil, Marise Barrymore, Buffalo Bill Cody…all those were important people that played in the theater. It’s also been a center for local history as well, you know local artists, local performances.”

The Historic Thalian Hall is still very much in use today, with over 250 performances each year. If you’d like to see this piece of historic stage art, and perhaps a performance as well, you can view performance times at www.thalianhall.com. For Public Radio East, I’m Zannie Owens.